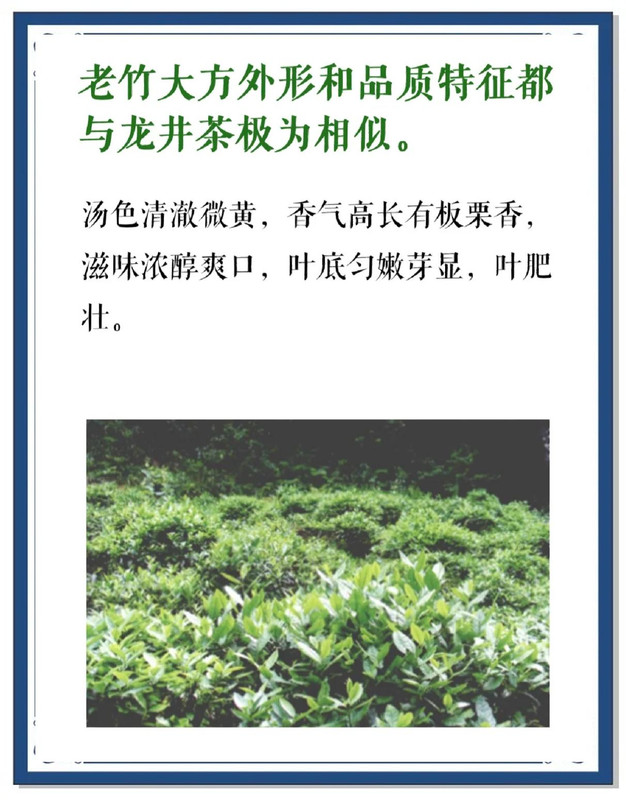

Nestled in the mist-clad peaks of Anhui Province’s Tianmu Mountains, 老竹大方 (Laozhu Dafang) has captivated tea connoisseurs for over four centuries with its striking resemblance to bamboo leaves and robust chestnut aroma. This historic扁形绿茶 (flat-leaf green tea), once a tribute to imperial courts, embodies the artistry of Chinese craftsmanship and the resilience of ancient tea traditions.

Origins & Legacy

Laozhu Dafang’s story begins in the Ming Dynasty, when a Buddhist monk named Dafang settled on Laozhu Ridge near Shexian County. Legend holds that he perfected a method to flatten and dry tea leaves, creating a brew so extraordinary it was named “Laozhu Dafang” (大方, meaning “great generosity”) in his honor. By the Qing Dynasty, it graced the tables of emperors, and in 1955, the “Dinggu Dafang” variant earned a coveted spot among China’s “Ten Famous Teas.” Today, it thrives in the same high-altitude gardens where it began, a testament to enduring quality.

Terroir: Where Mountains Meet Mist

The tea grows in a microclimate shaped by Laozhu Ridge’s 1,300-meter elevation, where:

- Climate: Annual rainfall exceeds 1,800mm, with fog enveloping the slopes 200 days a year. Spring temperatures hover between 12–18°C, ideal for slow bud development.

- Soil: Reddish-brown loam enriched by decaying granite, imbuing the tea with a mineral undertone.

- Cultivars: The local “Shida” variety, prized for its thick, downy buds, forms the tea’s backbone.

Craftsmanship: From Leaf to Legacy

Plucked from mid-March to early April, only the youngest bud and one adjacent leaf are harvested. The eight-step production includes:

- Withering (摊青): Leaves are spread on bamboo trays for 4–6 hours to reduce moisture.

- Pan-Frying (杀青): Leaves are tossed in iron woks at 130–140°C to halt oxidation, preserving their emerald freshness.

- Rolling & Shaping (揉捻): Artisans use palm pressure to roll the leaves into flat strips, resembling bamboo leaves.

- Baking (烘干): A two-stage drying process—first at 110°C to fix shape, then at 60°C to enhance fragrance—yields a moisture content below 5%.

Aesthetic & Sensory Journey

- Dry Leaf: Flat, jade-green strips with silver trichomes, resembling iron-cast bamboo leaves.

- Infusion: Brewed at 85°C, the liquor transforms into a golden jade, with leaves unfurling like blooming flowers.

- Aroma: Dominant notes of roasted chestnut and fresh bamboo, with a lingering sweetness.

- Mouthfeel: Full-bodied with a brisk astringency that mellows into a honeyed aftertaste, leaving a refreshing coolness in the throat.

Grading & Value

Laozhu Dafang is classified into four grades:

- Special Grade (特级): Uniform strips, dense silver down, priced at ¥650–¥800/500g.

- Grades 1–3: Include slightly larger leaves, with prices ranging from ¥100–¥460/500g.

Spring harvests command premiums, while autumn batches offer budget-friendly options.

Brewing Rituals

To honor its complexity:

- Teaware: Use glass or white porcelain to admire the “bamboo leaf” unfurling.

- Ratio: 3g tea to 150ml water (1:50 ratio).

- Infusions:

- First steep: 1 minute (awakens the leaves).

- Subsequent steeps: Add 30 seconds per infusion (up to 5 times).

Authenticity & Health

Counterfeits often lack the tea’s signature “iron-cast” appearance and chestnut aroma. Genuine Laozhu Dafang:

- Visual Check: Leaves should be uniformly green with silver tips.

- Cold Brew Test: Steep 1g in 50ml cold water; authentic leaves sink gradually, releasing a sweet aroma.

Beyond its cultural cachet, the tea offers:

- Antioxidant Power: Rich in EGCG, it combats free radicals linked to aging and cancer.

- Metabolic Boost: Caffeine and L-theanine synergize to enhance focus without jitters.

- Digestive Aid: Traditionally used to alleviate bloating after heavy meals.

Legacy & Modernity

Laozhu Dafang’s revival in the 1950s merged ancient wisdom with modern hygiene standards. Today, artisans experiment with floral infusions—jasmine or osmanthus—while preserving the classic “bamboo leaf” aesthetic. As a UNESCO-recognized cultural heritage product, it remains a bridge between China’s past and its dynamic tea scene.

From imperial courts to contemporary teacups, 老竹大方 endures as a testament to Anhui’s terroir—a living poem written in jade and fire.