China’s ancient kilns are the silent poets of its cultural history, each firing a unique verse in clay and fire. From the ethereal hues of Ru ware to the volatile splendor of Jun glazes, these kilns collectively narrate a story of innovation, aesthetics, and societal evolution. This article explores the most revered kilns of ancient China, unraveling their technical mastery and cultural resonance.

1. Ru Kiln: The Ephemeral Masterpiece

Emerging briefly during the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127), the Ru Kiln in Ruzhou, Henan, produced what is often deemed the zenith of Chinese ceramics.

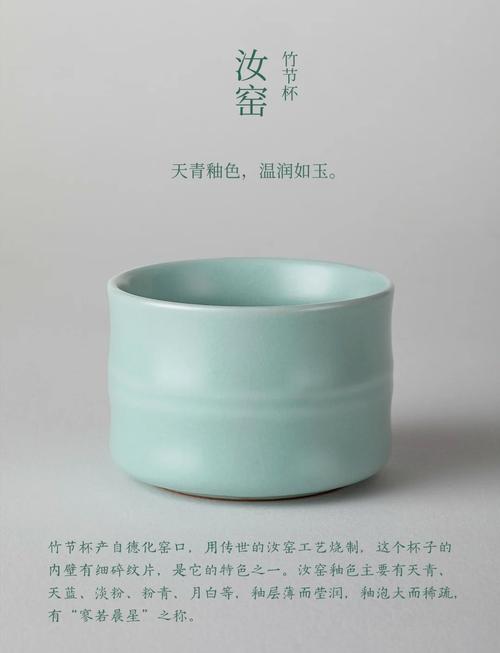

- Aesthetic Ideal: Ru ware epitomizes understated elegance, with its “sky-blue” glaze (tianqing) evoking the serene color of a twilight sky. The glaze, enriched with crushed agate, shimmers with a luminous sheen, while delicate “crab-claw” cracks (xiepiwen) add texture without disrupting harmony.

- Rarity: Only about 65 Ru pieces survive today, their scarcity heightened by the kiln’s destruction during the Jin-Song wars. Each piece, like the “Ru Ware Lotus-Shaped Bowl,” is a museum treasure.

- Cultural Symbol: Ru ware’s monochromatic purity resonated with Song Dynasty literati, who saw in its minimalism a reflection of Confucian modesty and Taoist transcendence.

2. Guan Kiln: The Imperial Voice

Established under Song emperors, the Guan Kiln (Official Kiln) served as the ceramic voice of the court.

- Dual Legacies:

- Northern Song Guan: Located near Kaifeng, it produced ceramics with “purple mouth and iron feet” (zishou tiezue), where the glaze thinned at the rim to reveal a purplish base, and the foot remained unglazed, showing a dark iron hue.

- Southern Song Guan: After the court fled south, kilns in Hangzhou revived the tradition, refining glazes to a “jade-like” luster.

- Technical Innovation: Guan potters mastered “cracked ice” glazes (binglie), where intentional crazing mimicked the fractured beauty of winter ice.

3. Ge Kiln: The Enigma of Fractures

Shrouded in mystery—no definitive kiln site has been found—Ge ware captivates with its “golden thread and iron wire” (jinsi tiexian) crackle.

- Glaze Secrets: A glossy, milky glaze conceals a network of fine cracks (jinsi) and thicker, dark fissures (tiexian), created by controlling cooling rates to induce differential shrinkage between glaze and clay.

- Philosophical Depth: The fractured surface became a metaphor for resilience—like life’s trials, the cracks enhance, rather than mar, beauty.

4. Jun Kiln: The Alchemist’s Dream

Jun Kiln, active from the Song to Ming dynasties, transformed kiln accidents into an art form.

- Yao Bian (Kiln Transformation): By introducing copper oxides into the glaze, Jun potters achieved iridescent hues of purple, crimson, and azure, with each piece emerging as a unique “fire miracle.”

- Iconic Forms: The “Jun Rose-Purple Drum-Shaped Basin” exemplifies this unpredictability, its surface swirling with colors like a molten sunset.

5. Ding Kiln: The White Perfection

Hailing from Quyang, Hebei, the Ding Kiln redefined white porcelain.

- Technical Triumph: Using a fine, ivory-white clay, Ding potters achieved translucent walls and thinness rivaling paper. The “Bai Ding” (White Ding) glaze, smooth as jade, became the standard for white porcelain.

- Decorative Flourish: Ding ware pioneered carved and molded designs, from floral sprays to mythical beasts, with patterns so precise they seem machine-made.

6. Beyond the Five: The Kilns That Shaped a Nation

- Jingdezhen Kiln: The “Porcelain Capital” of Jiangxi, active since the Han Dynasty, perfected underglaze blue (qinghua) during the Yuan Dynasty, laying groundwork for Ming Dynasty masterpieces like the “Chicken Cup.”

- Cizhou Kiln: In Hebei, Cizhou potters rebelled against monochromy, pioneering “white-ground black flower” (baidi heihua) designs using iron-based pigments, akin to ink paintings on porcelain.

- Longquan Kiln: In Zhejiang, Longquan’s “celadon” (qingci) achieved a jade-like green glaze, with the “Guyue” (Ancient Moon) style becoming a symbol of Song Dynasty refinement.

Cultural Resonance

These kilns were not mere factories but cultural crucibles. They reflected Song Dynasty’s “four arts”—qin (zither), qi (chess), shu (calligraphy), and hua (painting)—where ceramics joined the elite’s pursuit of harmony. A Ru bowl was not a utensil but a meditation on impermanence; a Jun vase, a celebration of nature’s caprice.

Legacy and Revival

Though many kilns fell silent by the Ming Dynasty, their spirits linger. Modern artisans, like those at Jingdezhen’s “Tenmile Kiln,” revive Ru glazes using ancient clay recipes. Museums worldwide, from the British Museum to the Palace Museum in Beijing, house these treasures, ensuring the flame of China’s ceramic heritage never dims.

In every crack, hue, and curve, China’s ancient kilns whisper the secrets of a civilization that found eternity in the ephemeral. They remind us that true artistry lies not in perfection, but in the courage to let fire and clay compose their own symphony. 🏺